Of Cowboy Mystique and Cattle

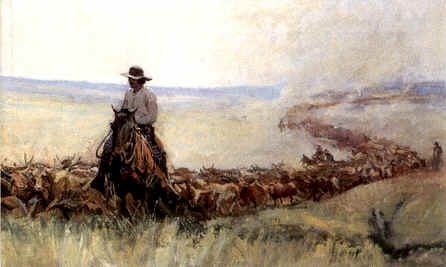

Cattle drives have captured the popular imagination around the world. In great part this interest was originally inspired by the biggest cattle drives in the history of the world which took place in the American West, but the great glory days hardly lasted a generation from the end of the Civil War to the 1890’s. The courage, determination and resourcefulness required to overcome the enormous obstacles and the multiple dangers faced were epical. Hostile Indians, crossings of flooded rivers, vast waterless plains, outlaws and stampedes were constant threats. The scale of operations was enormous. Millions of cattle were moved from Texas as far north as Montana and it took thousands of men and tens of thousands of horses to accomplish it. The riders performed exceptional feats of horsemanship and were mounted on courageous, athletic horses many of which were descended from wild mustang stock. The appeal of the era gave rise to movies like “Red River” and “Lonesome Dove” and has been the subject of countless songs, poems, short stories and books.

These cattle drives are responsible for a large part of the “cowboy” mystique which seems to have taken the place once held in European history by the Odyssey and the legends of King Arthur. Science fiction may be eclipsing all that now and one begins to wonder if society isn’t losing its grip on reality. Certainly there was much exaggeration at times in the accounts of those great cattle drive days, but many of the cowboys truly were heroes and real events were often stranger than fiction; making hyperbole superfluous. One can’t say the same of Star Wars.

As America started to recover from the devastation of the Civil War, its appetite grew for beef. By 1869 the first transcontinental railway had been completed and transportation of live beef from the West in large numbers to Eastern markets became practical. In Texas the cattle herds had grown to many millions and there was no way to market them properly. Fearsome Indian cavalry like the Comanche and Sioux had managed to hold up expansion for decades and had blocked routes to the north where there had been little market anyhow. Now with the dwindling of the buffalo which had been their livelihood and attacks from the US Army the power of these mounted tribes was weakening and a still perilous path to the north was opening. Would be ranchers from, Kansas to Montana needed cattle and rail heads in Kansas could take beef eastward. Thus the great drives began, reaching a peak in 1884 when an estimated 800,000 head crossed the Red River in Texas to move north.

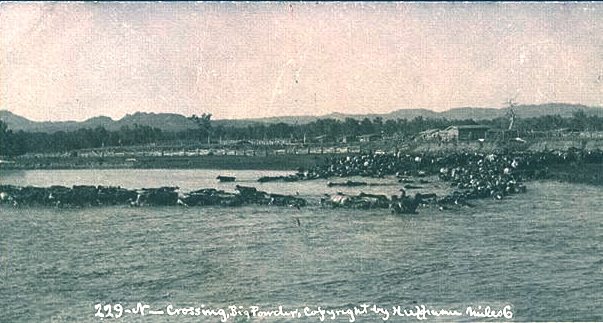

An N Bar herd crossing Powder River, 1886

photo by Laton Alton Huffman

Courtesy of Wyoming Tales and Trails

By the mid 1890s the Great Plains were pretty well settled. Barbed wire fencing was everywhere. The railways made access far easier and the Homestead Act of 1862 enabled settlers to acquire land west of the Mississippi free simply by living on it and improving it. The lawless, chaotic, traumatic days of the West drew to a close with amazing speed. Custer’s Last Stand, the Hole-in-the-wall Gang, the great herds of buffalo and unrestricted range were only memories. The era of the great drives, like that of the buffalo hunter and the mounted Indian warrior, glittered brightly for a brief moment in history, flickered and died, but left behind a fascinating legend and a world forever vastly changed.

Though the great cattle drives from Texas are history, there is still plenty of practical work being done on horseback by cattle ranches where the terrain is often too difficult for motor vehicles and a working cowboy is very much a necessary part of the scene. The fertile fields of Iowa may only need an acre or so per cow, but in Wyoming it might be more like 100 acres or even more and the land may be cut up by deep gorges, forests and mountains. Some grazing takes place on wilderness land where motors are forbidden. Dividing cows in a herd is another job best done on the back of a good cow horse and this is often required where cattle are grazing over big areas in National Forest or on BLM land. All along the Rocky Mountain area of the West the transhumance or moving of stock in spring and fall to and from the higher mountains is still vital to the operation of most ranches which depend on having their stock graze in the high country during the summer so that they can grow feed for the winter in the lower valleys.

Rounding up cattle in the fall requires riders

to go to some difficult places.

Photo credit Don Pettingale

These seasonal movements are usually over quite a short distance and sometimes are now accomplished partly by trucking until the roads give out. Drives along highways for long distances and through towns are mostly a thing of the past. Hauling by truck takes less weight off cattle and costs less than driving if the distances are more than 20 miles or so and good roads exist. Nevertheless this still leaves plenty of cattle work to do on horseback. Those who wish to work as cowboys for a time can still do a cattle drive in Arizona with a purpose because the Long Valley Cattle Drive has no viable roads and still requires a long drive on horseback.

Most of the drives into the high country in late spring or early summer take only a day or two, but the cows need to be dispersed from time to time and moved from pasture to pasture so that no places are overgrazed. The fall roundups at the Bitterroot Ranch are another story and it takes a full week to round up the cows and bring them down. The cows are dispersed over 60,000 acres of difficult terrain going up over 10,000 ft. with forests, streams and gorges. Even after a week some are usually not found. Now that wolves have been reintroduced in the Greater Yellowstone area the cattle are harassed and dispersed more than ever. Each year a few are killed by wolves or bears and they lose weight and become wilder when they are harassed. The cattle can be tucked away in hidden alpine clearings or in the fringes of the forest where they are very hard to find.

By Bayard Fox